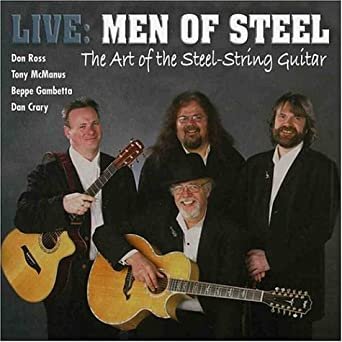

Live: Men of Steel -- The Art of the Steel-String Guitar (Thunderation, 2003)

NOTES on Song

Reflections on music by a lifelong writer and musician. www.mddunn.com

Sunday, August 21, 2022

Mini-Review: Live Men of Steel

Saturday, July 30, 2022

Linda Manzer and the Spirit of the Guitar

The story goes that Linda Manzer got hooked on instrument building after making a dulcimer for herself in high school, or shortly after, in art college maybe, and never gave it up. Manzer has built several guitars for Bruce Cockburn, and he has purchased others second hand. Currently, Bruce plays two Manzer six strings and a twelve string, as well as the charango, which was the first instrument she built for him. But Cockburn is just one of Manzer’s high-profile clients. Pat Metheny, Stephen Fearing, Mary Lynn Hammond are just some of the remarkable musicians to play her instruments. She has built close to thirty instruments for Pat Metheny alone, including a sitar-style guitar, baritones, and “The Pikasso,” with four necks, two sound holes, and forty-two strings.

In the early and mid-70s, players like Michael Hedges, Richard Thompson, John Renbourn, and Bruce Cockburn were pushing the limitations of the instrument. Jean Larrivée responded by building an acoustic guitar with a cutaway design to give the player access to the upper frets. His first models to incorporate the design were called the Larrivée C-series. Bruce Cockburn received one of two of these early cutaways, which perpetuated the idea that the C-series had been made specifically for Bruce, a story he denied in an interview with Acoustic Guitar Magazine.[1]

But David Wren, a luthier apprenticing at the same time as Linda Manzer, remembers it differently. Cockburn had been visiting Larrivée’s shop in Toronto quite regularly in the early 1970s. In an interview with Jon Carroll from December 17, 2000, posted on The Cockburn Project, David Wren remembers that Bruce “requested a cutaway, which at that time was a completely outrageous idea. I had never seen that on a flat-top steel string.”[2] So, either the first steel-string acoustic guitar was made for Bruce Cockburn, or he was given one of the first made.

She needn’t have

worried. Players who tried the wedge design were immediately taken with the

comfort it offered. Cockburn found that the modification helped relieve a

pinched nerve in his elbow. And soon, other luthiers were adopting the design

into their builds.

“I was very discreet

about it for the first few years, but once people started copying the design I

realized I had to attach my name to it so people would know it was my idea, and

that I wasn’t copying someone else,” says Linda.

Rather than trying

to prevent other luthiers from using the modification, Linda made it open

source, for a price. “At the beginning, I gladly excepted a bottle of wine each

time somebody used it. If I had kept that up I would have quite a wine

collection,” she says.

The wedge is now

open for anyone to use if due credit is given to its inventor.

Guitar-making is

akin to a spiritual practice for Linda Manzer, and players speak of her

instruments as living beings. There is a bit of animism at play with

instruments and musicians. An instrument needs to be played, otherwise they

quite literally go to sleep. The wood becomes rigid. After a prolonged time

without use, the instrument will sound thin and become less playable. The more

regularly an instrument is played, the more it opens up. A good guitar gets

better with age, if consistently played. And the guitar will change in response

to the specific player. Wear on the fret wires and fretboard under the strings

and the back of the neck reveals the favorite positions of the guitarist.

Slowly, a guitar will mirror the player’s habits. Many guitar players claim an

instrument takes on the spirit of the player.

“I actually do

believe objects can hold a little essence of the person they spend a lot of

time with,” says Linda Manzer. “I have personally experienced getting a

guitar back from somebody for repair and feeling as if they are in the room

with me. After a few days that leaves, and I infuse the guitar back with a

little bit of me. It sounds a little hokey, but I bet someday in the future

what I feel intuitively will be scientifically proven.”

She does not produce a great many guitars, and

her instruments, new and used, are prized among players. These are not entry

level instruments. A used instrument, like the 1979 model formerly owned by

Stephen Fearing, has been listed for $14,000 US. A new Manzer guitar can go for

$25,000 and more. The building process can take eighteen months. It is slow,

meticulous work.

In 1989, Stephen

Fearing was looking for a new guitar. His Guild D-35 was falling apart. He’d

heard of Linda Manzer through his friend the late Willie P. Bennet, for whom

Fearing’s current band Blackie and the Rodeo Kings began as a tribute. As luck

would have it, Linda had a guitar for sale.

“I like the idea of

hand-built guitars,” says Fearing. “And I was definitely aware of Larrivée.

Somehow, I knew that Linda had studied with Larrivée, which made me curious.”

Fearing paid $2,900

for his first Manzer guitar, which, he says, “was a king’s ransom at the time.”

He played that guitar for thirty years until, on the anniversary of that purchase, Linda Manzer presented Fearing with a new guitar. “I’d been trying to figure out how I could afford a new one,” he says. Astonishingly, a fan willed Fearing a Linda Manzer guitar that had not been played. It had sat on a stand in the corner of a room for years. When Stephen Fearing received it, the guitar needed some work. He brought it to Tony Duggan-Smith, who performed a neck reset, which involves removing the neck from the body, adjusting the joint, reattaching, then refinishing the sound board. The guitar also had a mother-of-pearl unicorn on the headstock, which Stephen had removed.

Linda took it back in trade for the new guitar.

“It’s an astounding

guitar,” says Fearing of the new instrument. “It has the wedge, and it has my

signature beautifully inlaid on the twelfth fret. She cut it out of mother of

pearl. Linda said she didn’t breathe for an hour. Mother of pearl is super thin

and very brittle. She glued a piece to thin plywood then used a Dremel tool to

cut around my signature. Astounding.”

In recent years,

Linda Manzer has been building guitars for exhibitions in art galleries. It is

kind of full circle. Before she joined Jean Larriveé’s team at the age of

twenty-two, Linda studied painting in college.

One recent project included six fellow Larrivée protégés, whom Manzer calls her “tribe of littermates,” each building a guitar in honour of a member of The Group of Seven. Linda’s guitar is a tribute to Lawren Harris and his painting Mt Lefroy (1930). The main part of the guitar is a traditional six string, but a shorter, eight-stringed harp neck juts up toward the player like the mountain peak for which it’s named. The guitar body is painted white like winter on Abbot Pass and gradually becomes icy blue toward the harp neck, which is shaped to resemble Mt. Lefroy itself. The guitar is now part of the Group of Seven permanent holdings at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario. Bruce Cockburn surprised Manzer by composing a piece for the instrument called “The Mt. Lefroy Waltz," which was later released on his Crowing Ignites album with a band arrangement of bass, drums, cornet, and electric guitar, but no little harp.

“I tried to come up with something icy

sounding,” Cockburn told The Globe and

Mail’s Brad Wheeler. “The guitar favours the higher frequencies, and I

tried to write that into the piece. It played

very well. I was even able to use the ‘harp’ strings that are part

of its architecture.”[4]

Manzer continues to

build for players as well and is excited about the quality of luthier-built

guitars in Canada at present.

“I notice other

builder’s designs,” she says. “But I don’t particularly study them. I am more

interested in building techniques and how other builders technically assemble

their guitars, the tonal choices they make. There are so many great and

innovative builders out there right now. It’s nice to see everyone sharing

ideas and technique.”

[1] Acoustic Guitar Magazine. (January 28,

2015) [Video] https://youtu.be/W8sYV_eo7_Y?t=1420

[2] Carroll,

J. (December 17, 2000). Interview with David Wren. http://cockburnproject.net/news/001217davidwren.html

[3] Pikasso.

(n.d.) https://manzer.com/guitars/custom-models/pikasso/

[4] Wheeler, B. (December 31, 2016). Masterwork

guitar exhibit honours Group of Seven. The

Globe and Mail.

Wednesday, March 10, 2021

Cockburn Conspiracy #43 – The Moranis Deception

Few secrets in Canadian history have been as closely guarded as the Cockburn-Moranis connection. Here now, after minutes of research and groundless speculation, I make the stunning claim that songwriter Bruce Cockburn and actor Rick Moranis are in fact the same person!

I offer as evidence the following:

1. Just look at them! These images have not been altered.

"Bruce Cockburn" "Rick Moranis"

2. Have you ever seen them together? I have not, and so I conclude that my premise is sound. Furthermore, should photographic evidence surface of the Canadian icons together, rigorous analysis will be necessary to establish authenticity. Deep fake technology and simple image editing programs could easily alter such documentation. Even if a photograph surfaces of the two together, I have made up my mind already.

3. “Rick Moranis” plays guitar! Look no further than this

recently uncovered document of Moranis –

or is it Cockburn in his Moranis persona – playing with The Recess Monkeys at a high school dance. It is curious that Cockburn has never acknowledged his tenure as lead singer of The Recess Monkeys.

One might challenge the video evidence: “Wait. I’ve seen Bruce

Cockburn play guitar. He plays right-handed, while ‘Moranis’ is playing

left-handed.”

Good point, but consider that Bruce Cockburn is in fact left-handed. He claims to have never learned to play left handed. Witnesses attest to seeing Cockburn sign autographs with his left hand. Add to this anecdotal evidence, the fact that he wears a watch on his right arm, which is common among sinistral people.

Furthermore, "Moranis" uses two fingers for his G-chord in a manner similar to Cockburn, by placing a thumb over the top of the fretboard.

Observe Cockburn/Moranis displaying his left-handedness in public. Photo by Brent Reid.

4. “Rick Moranis” plays guitar about as well as Cockburn might left-handed after playing right-handed for 60 years. But Moranis is playing, like Elizabeth Cotten and so many other lefties, a guitar strung for a right-handed player. The high strings are on top. Jimi Hendrix played a guitar made for a right-handed player but strung it traditionally with low strings on top. Left-handed guitars were hard to find and players adapted.

5. When given the opportunity to respond to these allegations, Cockburn did not deny the likeness. I phrased the question slyly,

so as not to reveal that the charade has been exposed, by asking who might play him

in the movie of his life: “Back when SCTV was on the air, everyone hoped that

Rick Moranis would do a Cockburn impression,” I said.

The vagueness of Cockburn’s response is telling: “I seem to recall that having happened. It’s a hazy memory, which I don’t fully trust, but I have a mental picture of Moranis wearing a white leisure suit with a trio of female backup singers, singing a kind of lounge version of 'Wondering Where the Lions Are' against a hokey 'nature' backdrop. In my memory it was very funny. I wonder if I actually saw that or dreamt it...”

Notice his careful choice of language: “seem to recall,” “hazy memory, which I don’t fully trust,” and “I wonder if I actually saw that or dreamt it…”

I am willing to consider, based upon Cockburn’s obfuscation around the Moranis inquiry, that he may be unaware or only partially aware of his alter ego. Perhaps the songwriter enters into a fugue state in which he becomes Rick Moranis. Could this be the information that Cockburn suggests CSIS has on him at the end of the song “Slow Down Fast”? The investigation continues.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/KTKU55TAINFTXPTY6WOGEK2URE)

Photo as published in The Globe and Mail, credit unknown

Friday, February 19, 2021

NOTES on Song: "The Song of Wandering Aengus" by W.B. Yeats

I have

been thinking of a poem by William Butler Yeats called “Song of Wandering Aengus.”

It’s a ‘glimmering girl’ poem. Actually, it is the glimmering girl poem. Another term for it is the Enchanted

Visitor, removing the gendered language and image. Irish literature, especially

the old stuff, is all about fae infatuation and otherworldly visitation. Faerie

folk snatch humans, humans cross into the Other Place while in the woods, or in

a dream, or exiled from community. In this poem, the speaker and title character meets a strange figure in the woods and spends the rest of his life trying to find her.

The glimmering girl motif repeats through Yeats’ early poems. He was thirty-five in 1899, when he wrote “Song of Wandering Aengus.” For a Christian male of his era, thirty-five is a challenging age. It's two years passed the age of Christ. Two years passed the age of Epiphany. It's the age when Dante got lost in the dark woods, a time to take measure. There is a well-known biographical parallel in Yeats’ life for the vanishing vision of desire: his unrequited love for the revolutionary Maud Gonne. “Song of Wandering Aengus” is about the ‘one that got away,’ if read biographically.

I don’t favour biographical criticism. Undoubtedly, the circumstances of the writer’s life will influence the writing. There can be no poem without a life to generate that poem. As Leonard Cohen once said, “Poetry is just the evidence of life. If your life is burning well, poetry is just the ash.” Studying a poem to understand the poet’s life is reverse engineering, forensics. Studying the poet’s life to understand the poem is extrapolation, projection. Elements of these approaches can be helpful, but too much biography in interpretation and application gums up the works. It distorts reception and interferes with the mind’s ability to integrate the poem into one's understanding.

Yeats’ poem is remembered, mostly, for its last lines: “the silver apples of the moon / the golden apples of the sun.” Degrees have been doled out in the business of applying meaning to those phrases. Ray Bradbury borrowed the sun line for the title of a short story collection. In one of those stories, a ship with a giant scoop, like a cosmic backhoe, is sent to bring back samples of the sun. That is all I remember of the story and would have to track my Bradbury books to their hollow, which I am not willing to do at the moment, in order to expand on the story. So you’ll have to take my word for it. I must have read the story, or maybe a teacher read it to us in class as they used to do, because I remember gassing on the idea of being able to walk on the sun. Given the right boots, you could walk on the sun. If the sun was matter that can be scooped into a bucket, then it can be walked on too. I must have been quite young when I heard that story.

Aengus, the speaker in the poem, could be the Old Irish god Aengus, a lover, healer, and patron to the poet. Aengus appears in Yeats’ poetry frequently. The Aengus we meet in “Song” is restless:

I went out to the hazel wood,

Because a fire was in my head,

Yeats hits the reader with magick from the first line, although we might not see it at once. He leaves the lines open for magick, might be a better way of stating it. Hazel is strongly associated with Earth magick. It’s the dousing wand. Hazel finds water, in the old way of living in the world. The man who doused for water behind my childhood home [more on this later] used hazel branches. And doesn’t Sybill Trelawney, the scrying professor in the Harry Potter series I can never read, wield a hazel wand? Yeats gives Aengus a wand, too:

And cut and peeled a hazel wand,

And hooked a berry to a thread;

The four lines quoted above make up the first half of the first octave (eight lines stanza) in the poem. The octave structure is interesting because Yeats alters the rhyme in the last four lines of each stanza. The effect is to create internal quatrains (four-lined stanzas) within each of the poems three octave stanzas. The rhyme scheme runs ababcded in the first two stanzas, but Yeats breaks the pattern in the third octave. The effect of this structure creates a turn in the first octave. We get:

I went out to the hazel wood,

Because a fire was in my head,

And cut and peeled a hazel wand,

And hooked a berry to a thread;

And when white moths were on the wing,

And moth-like stars were flickering out,

I dropped the berry in the stream

And caught a little silver trout.

It seems easy enough. Aengus has a lot on his mind, wakes up early, goes fishing. But why, Aengus, why? “Because a fire was in my head,” he tells us. Where better to go with a fire in one’s head than to a forest of water-finding trees?

Aengus makes a fishing pole might be a good way to describe the set up for the octave’s turn. Yet, it is not a pole, or a rod, but a wand, which points the reader to the ritual beneath the action. And when he baits the hook, we don’t see the hook. There is no hook; it’s the act of hooking a berry to a thread that we witness.

White moths arrive to mark morning and to replace the stars as they fade. Here Yeats gives an internal rhyme, the only overt internal rhyme in the poem. It’s like he is offering a transition through the broken abab pattern in the first four lines: “[…] on the wing / […] flickering out.”

The last end rhymes bring it all together: “[…] flickering out / [,,,] silver trout.”

Yeats has hooked us.

The second stanza introduces the “glimmering girl” everybody has been waiting for:

When I had laid it on the floor

I went to blow the fire a-flame,

But something rustled on the floor,

And someone called me by my name:

It had become a glimmering girl

With apple blossom in her hair

Who called me by my name and ran

And faded through the brightening air.

It’s a quaint idea, perhaps offensive in our age. The fish becomes a woman – “girl” -- with no less than “apple blossom in her hair.” And she knows the dude’s name! Calls it out, runs off, or vapourizes. Of course, he spends his life searching for her, the exemplar of beauty, a woman from a fish, a woman who knows him. We have to step back from the specifics. Yeats saw a “glimmering girl” because that is what the old stories told him to see. Likely that is what his libido wanted him to see as well: a magical woman pulled from a stream, the great fish of desire calling to him. This is the enchanted visitor. For another poet, it could be a man from an eel. From Yeats, we get the glimmering girl who fades in “brightening air.”

It’s not clear if “brightening” is from the sun as it declares morning, or if it is meant to describe a less literal transformation. Brighten can mean ‘to purify’ as well as to make brighter. Yeats applies the present participle verbs “glimmering” and “brightening” as adjectives to shine up the girl and the air, respectively. Light manifests in these lines, and the actions of glimmering and brightening are embodied in the fish-girl and in the air.

The last octave tells us that the Aengus we’ve been listening to is looking back, although still actively searching for the girl he saw by the brook:

Though I am old with wandering

Through hollow lands and hilly lands,

I will find out where she has gone,

And kiss her lips and take her hands;

And walk among long dappled grass,

And pluck till time and times are done,

The silver apples of the moon,

The golden apples of the sun.

The reader misses out on Aengus’s adventures. We don’t know how long he has searched, or where the search has taken him beyond “hollow lands and hilly lands.” And maybe those descriptions are enough. The alliteration of hollow and hilly is quite lovely. There is also something jarring about the image of “hollow lands.” Were these places void of substance, or literally hollow? Both? To what degree? The lines in the last verse are beautiful, I think, and contrast the controlled narative voice in the first stanza. Remember the “hazel wood” and “hazel wand”? These are not easily spoken. The word “hazel” alone requires some quick stretching. By the last verse, the voice is lyrical: “old with wandering,” “long dappled grass,” “pluck until time and times are done.” The poem demonstrates a song manifesting from events. By the end, Aengus is singing.

The verb “pluck” is an interesting one. If this poem were a limerick, “pluck” might give us pause to wonder where it is going. Yeats uses “pluck” with intention. The apples being plucked are metaphorical apples. These lines, the most famous of the poem, offer an apotheosis. The entire poem rises to these lines. It ends with the speaker looking into the future with his beloved. In his fantasy, they will be together until not only they run out of time but until the end of "times” as well. This brings another motif in the poem, a nod to the carpe diem motif that runs through western literature. Long translated as “seize the day,” the phrase carpe diem instructs to grab all one can. Robin Williams’ school master in Dead Poet’s Society instructs his students to "seize the day" to, quoting Henry David Thoreau, “suck all the marrow of life.”

But it is a subjective translation of carpe diem that has been adopted by the modern west. ‘Seize the day’ is the language of conquest, of war, violence. It’s the perfect motto for a culture obsessed with accomplishment and assertive action. However, “carpe” does not have to be translated as “seize.” It is more similar to the word, you guessed it, “pluck.” The original proponents of carpe diem were telling us to pluck the day, like a flower, like an apple. The phrase comes into English from Horace’s Ode I.11, in which he advises the reader: “[…] Time goes running, even / As we talk. Take the present, the future’s no one’s affair.” The Ode reminds the reader to tend to the moment, to pluck the days like apples from trees.

And that’s where Yeats has led us and led Aengus, being with a loved one, gathering the moonlight in the evening, the sunlight of the day, until “time and times are done.”

The Waterboys cover the poem beautifully on An Appointment With Mr. Yeats (2011, Proper Records), with Mike Scott changing a word or two. Scott’s revisions, I believe, make the poem stronger. He replaces the repeated “floor” from the second verse and alters the third line entirely. In Yeats, we have:

When I had laid it on the floor

I went to blow the fire a-flame,

But something rustled on the floor,

And someone called me by my name:

Mike Scott, lead singer and main writer of the Waterboys, refines the verse:

When I had laid it on the ground

I went to blow the fire a-flame,

But something made a rustling sound,

And someone called me by my name:

The rhythm is maintained, but the lines become more interesting with the modern “ground” rhyming with the “sound” of the fish becoming the “glimmering girl.” Scott’s alteration to the text also gives us another present participle in “rustling” to match the glimmering and brightening in the same verse. Altered too is one of Aengus’ plans upon meeting up with his infatuation. Yeats has Aengus “take” her hand, which has a degree of possessiveness to it and implies marriage. Mike Scott allows Aengus only to “touch her hands.” It is more gentle and more of a question than an act of conquest.

Poetry and song are indivisible. With “Song of Wandering Aengus” by The Waterboys, we have the poem’s full expression. It’s a rebirth for a poem that is usually remembered only for its last lines, and then, often, in mockery for its grandeur and antiquated diction. The song does not quite reach to the heights of emotion of The Waterboys “big music,” but Sarah Allen’s flute certainly helps bring the song’s energy to the mythic level it deserves.

Coming up: Through Arawak Eyes by David Campbell

Court and Spark by Joni Mitchell

and, "The Trouble With Musical Friends"